A former prison with a tumultuous past, the Workhouse Arts Center now serves the community and hosts the Workhouse Military in the Arts Initiative (WMAI).

Despite the notorious period helping spur a constitutional amendment, the purpose of the Workhouse began with noble intentions.

Founded by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1910, the site on the Occoquan River in Northern Virginia was an agricultural work camp meant to alleviate overcrowded D.C. prisons and rehabilitate men imprisoned for minor offenses.

After building the facilities using local clay, the inmates also cultivated fields and operated dairy, poultry and hog farms; orchards; a blacksmith forge; and a sawmill. Initially, the camp didn’t have fences and children from the community would even ride bikes through the grounds, says Workhouse historian Laura McKie.

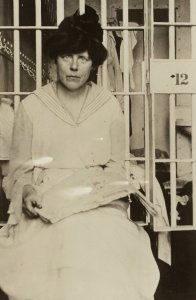

But the atmosphere changed as it grew and included violent inmates. In addition, a women’s facility separated from the main campus became the location of the “Night of Terror.” The notorious incidents occurred from Nov. 14, 1917, through January 1918 after suffragists picketing the White House infuriated then President Woodrow Wilson.

Arrested and taken to the Workhouse, the women underwent torture. Stripped naked and chained with arms overhead, they endured beatings, filthy conditions, and forced feedings until ill.

Their treatment made headlines, putting public pressure on the government to release them and support the ratification of the 19th amendment on Aug. 18, 1920. Despite the women’s exoneration, the Workhouse continued struggling with issues until closing in 2001. But once sold to Fairfax County, it became a haven for the arts, free and open to the public.

Debra Balestreri, director of the Visual Arts Education Program, says the center now boasts more than 100 studio artists and holds classes in visual, culinary and performing arts; fitness programs; festivals, and the Lucy Burns Museum honoring the suffragists.

Also offered is WMAI, a program for service members, veterans and their families to experience the therapeutic effects of art. As a Marine brat herself, as well as losing her boyfriend during the War on Terror, WMAI’s mission is personal for Balestreri. She also explains that WMAI operates in accordance with guidance from Americans for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts and research demonstrating art helps the brain reorganize and adapt.

More Artistic Inspiration: Coast Guard public affairs specialist tells Norfolk’s maritime story through art

“Participation in art, whether expressive, educational, or recreational, reduces stress and anxiety, while building resilience, coping skills, self-esteem, and well-being. Art also promotes meaningful relationships and is an effective means of communication when words simply will not do,” Balestreri said.

She also detailed some of WMAI’s free services:

-

Veterans Open Studi

-

Make & Take Workshops

-

Ceramics

-

Flameworking

-

Recovery Forge Blade-smithing

-

Wounded Warrior Project Outreach

-

Artist-In-Residence Program: Veterans become studio artist.

-

Warrior Way Gallery

Tiffany Rivera, an Air Force officer, enjoys taking advantage of WMAI. Though starting as an Air-Craft Battle Damage Repair Engineer for the C-17 Aircraft, she is now in D.C. learning a foreign language for her next assignment at the Hungarian Embassy.

She explains how she and her family immersed themselves in WMAI after attending a “Second Saturday” event where they “spent hours walking around, eating free food and meeting artists.”

Her daughter attended art camp and Rivera volunteered for Second Saturdays and Drive-In Movie nights. Then, her husband became a Workhouse studio artist.

“Art was new for me. I’m a black and white, numbers gal but noticed my kids’ spirits light up when hanging out in my husband’s studio. I wanted that feeling, so signed up for a ceramics class,” Rivera explained. “I was skeptical of art therapy. But my first class, it was just me, my wheel, and my mound of clay. I had no idea I was carrying so much stress until I had the opportunity to relax and focus on shaping my clay.”

Upon deeper reflection, Rivera describes the impact.

“I take pride in my wonky bowls and chipped coffee cups … they make me realize I don’t need to be perfect to be loved,” she said. “I don’t need to be perfect to be good at my job and my imperfections make me the unique person that I am. I got all of this out of ceramics.”

The Workhouse once imprisoning “women willing to die for the right to vote and be considered a citizen,” as McKie explained, now serves the public in a rehabilitative spirit originally intended, particularly the military community, a population protecting those same rights.

Read comments