Three Para athletes are using their platforms to establish equity in sports for retired service members.

Christy Gardner, Brad Snyder and Jen Lee overcame daunting adversity to inspirationally excel in the para sports arena, modeling hope to others who are in the process of healing.

“I’m really thankful to be partnering with Citi, to kind of make sure that we as Team Citi athletes kind of represent what success looks like on the other side of adversity,” Snyder said. “And making sure that that opportunity exists for others is really important to me. There’s definitely a journey, and there’s a lot of different things that come at you at different times.”

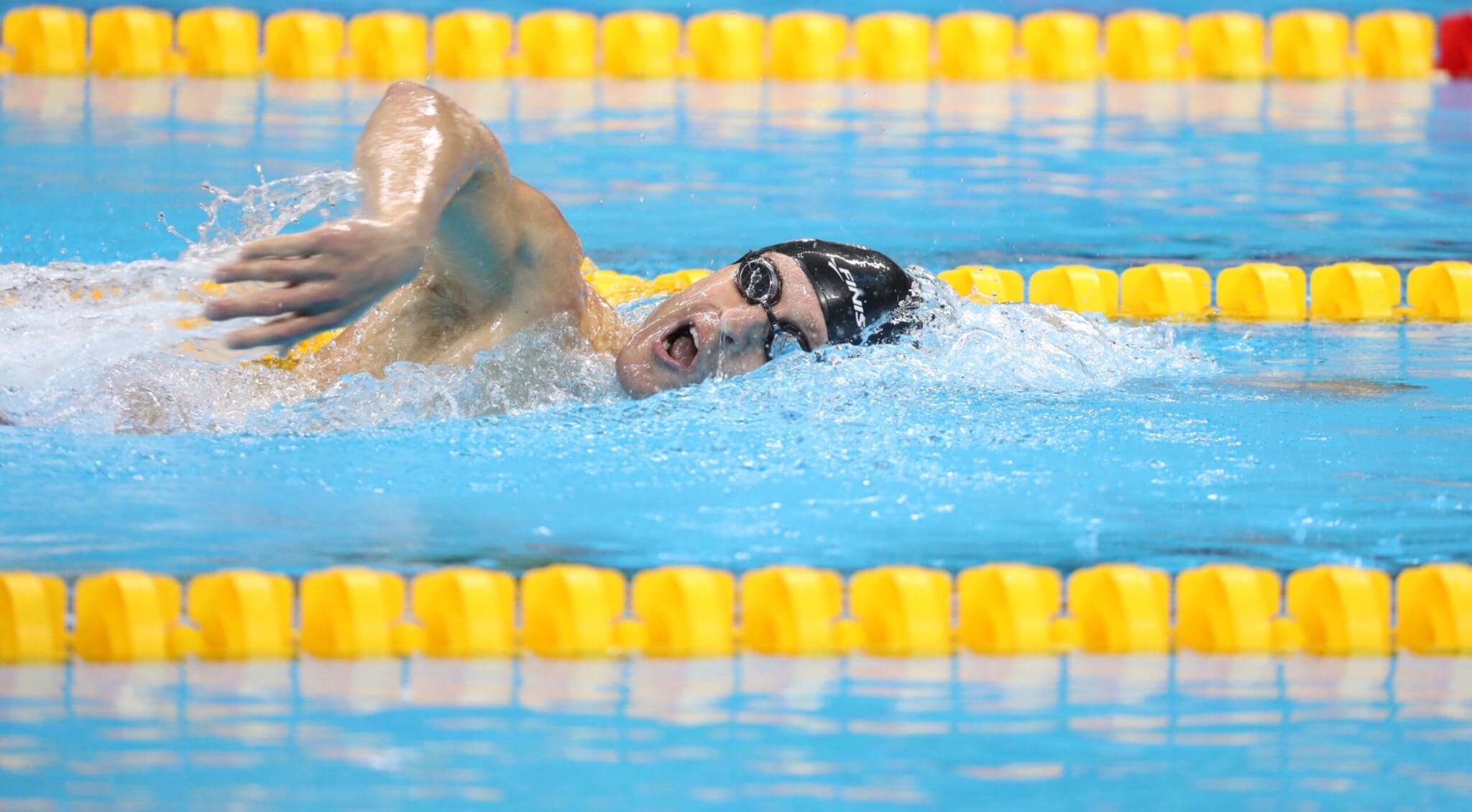

Snyder, who swam for the Naval Academy and has collected six gold medals and two silver medals in men’s Paralympic swimming, was six months into an Afghanistan deployment in 2011 when he stepped on a roadside bomb that detonated 18 inches in front of him. Death walked up alongside him, and an audit of his life began.

“So I kind of, you know, framed out what I was thinking about at that moment, was sort of a reconciliation of my life and an acceptance of my death.”

When reality set in, Snyder was able to walk away from the explosion but lost his vision.

“And then I remember before the helicopter came down, I was standing there, actually, and asked my buddy to take a picture of me because I wanted to see it,” he said. “And I had this thought that, ‘I wonder, like, how long am I going to be out for? A couple days, a week? Like, how long will it take to get better from this?’ It hadn’t occurred to me, at least at that point, that this was something that was going to be long lasting.”

Snyder was admitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he began to understand that his life had changed permanently and it was a matter of believing in modern medicine.

“Now, by virtue of the fact that I was injured in 2011, we as a society had gotten really good at figuring out how to get folks like myself who are wounded on the battlefield back into life in a meaningful way.”

Then there is the story of former soldier Gardner, a military police officer whose body was literally mangled.

“I’ve been in the lowest place you can be, and so it seems like everything else is so much better … someone asked my grandmother once if she was sad for what happened to me, and she goes, ‘You know, it’s terrible being injured but look at the life that’s afforded her.’”

The Team USA Para Ice Hockey co-captain and gold medalist — also a Citi-sponsored athlete — travels the globe competing in sports, a life unimagined, pre-injury. She served in the Army and sustained a jaw-dropping amount of injuries overseas (South Korea-demilitarized zone) in 2006 — fracturing her skull, cheek bones, jaw and nose, crushing the left arm and damaging internal organs and the spinal cord. She also lost both legs below the knees.

Gardner, who has been a member of the national hockey team team for 13 years and was the 2013 USA Hockey Disabled Athlete of the Year, said she had to begin her miraculous recovery at the third-grade level again and endured nearly six years of physical therapy, speech therapy and occupational therapy.

“You know, learning basics like the thing in the driveway with four tires … because I had significant brain injury.”

The Maine native met with an array of specialists, from neurology to orthopedics, and a polytrauma team. Their consensus comprised a three-page list of what Gardner would never do again, including living alone, cooking for herself, driving a car, riding a bike, swimming or taking a bath alone, lest she suffer a seizure and drown.

“So all of that honestly, really sucked … honestly, completely defeated when I was conscious enough or lucid enough.”

However, they advised Gardner to apply for a service dog, which turned out to be a good move. She ultimately acquired one, Moxie, who provided mobility assistance and seizure alert response.

“But more than that, she motivated me, mentally,” Gardner said, who is the founder, president and head of training for Mission Working Dogs. “She made me get up, made me move, kind of dragged me back into the world.”

And adaptive sports completed the process, allowing Gardner to now be a kind of ambassador.

“To show the world that what we can do despite our disabilities is such an incredible thing. Whether we’re motivating the next generation and inspiring the next generation of kids to come play at this level or to represent and let them know that they can, that this sport exists.”

Lee had been a multi-sport athlete growing up in the Bay Area, enlisting in the Army straight out of high school. Unlike Snyder and Gardner, Lee was injured in the U.S. while riding a motorcycle.

“So it was just a typical Saturday riding with four of my other colleagues…we rode to Jacksonville, Florida that morning, and on the way back, Interstate 95, I just happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

The Taiwanese-born sled hockey player was taken to a hospital in Savannah, Georgia, but the fracture he suffered and subsequent infections eventually resulted in the amputation of his entire left leg.

“And there’s a lot of questions of why me? Why did this happen? And then it didn’t matter if the wind was blowing in different directions or the rain or whatever, sunshine or rainbows. I just had a very frustrating time and just didn’t understand. They didn’t understand, you know, all this that was happening to me.”

Once Lee was transferred to the Center for the Intrepid at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio for rehabilitation, his outlook began to change. CFI provides care for OIF/OEF wounded who have sustained amputation or functional limb loss. Rehabbing alongside soldiers wounded during combat brought Lee inspiration and guilt.

“These men and women, they continue to want to serve their country … and that made me realize, like I have no excuse to make for myself … I didn’t feel like I belonged there because I wasn’t a Purple Heart recipient or a combat guy. So I wanted to prove myself that, ‘Hey. I can work hard as well.’ And if they’re taking 10 steps that day, I make sure I walk 11 steps with my prosthetic legs.”

Lee, a three-time gold medalist in sled hockey, is a member of the Army’s World Class Athlete Program and currently an outreach director for TheraV, an organization assisting amputee patients in managing phantom limb pain. He said he was shocked to discover a sport avenue in his post-injury life. A path for elite athletes with a disability.

“But then little did I know once I started competing in sled hockey and … travel league team, I realized how tough and competitive sports is and how athletic other athletes were that was not military and born with a disability.”

Lee said it connected him with his athletic past and enabled him to continue on his journey as a soldier-athlete.

“Because I was able to make the national team, but at the same time, continue on active duty, putting on my uniform and serve my country, represent my nation all at the time. So it was a really, really good blessing.”

Read comments