For a long time, army spouse Alexandria Robinson made playful jokes about her husband’s career in the GEOspatial INTelligence field. The job uses advanced radar technology, aerial imagery and electronic sensors to analyze battle areas and support combat operations.

“It’s a technical field, so I would always tease him and say, ‘oh, that’s kind of nerdy,” remembered Robinson. The mother of six had gotten a college degree in nursing. Still, she was surprised when she couldn’t stop asking her husband questions about what he was learning in his new GEOINT classes with American Military University.

“Finally, he said, ‘you know, you seem like you have a real interest in this, you could go to school for this too,” Robinson recalled. She decided to look into the classes and got hooked on Lidar, Light Detecting and Ranging technology.

“I was in awe. I thought it was the coolest thing in my life,” she said. “And I remember calling my husband, and I was like ‘Oh my goodness, this is just so cool, and he just smirked and said he’d be telling me that for a decade now.'”

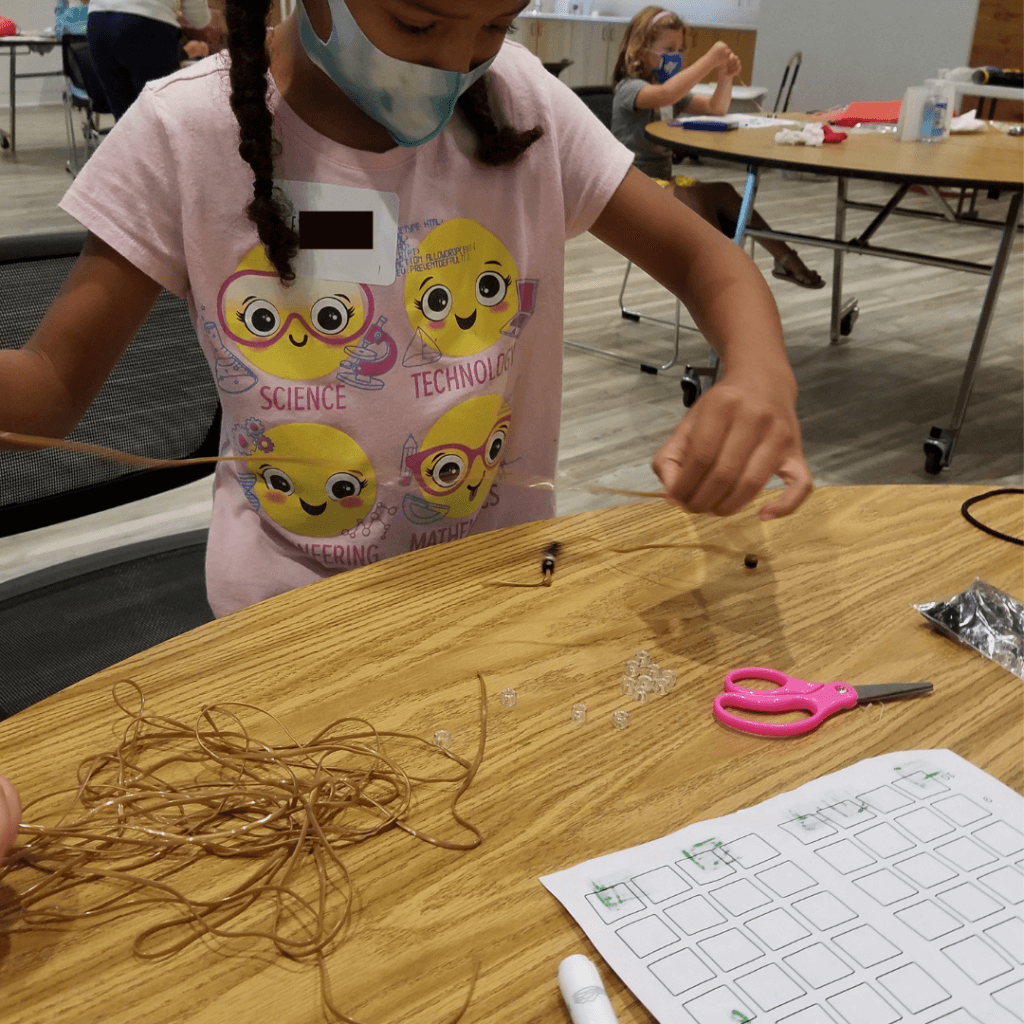

Recently she got an opportunity to translate her new calling into a paying job. Rosie Riveters, a nonprofit that hosts science, technology, engineering and mathematics programming for young girls, was recruiting military spouses with STEM education to teach a new pilot program near Washington D.C. at Fort Belvoir. Robinson was hired as an instructor, and now she shares her passion with young military girls in a United Service Organizations (USO) classroom.

“Our girls have a really great time. Last week we had a little bit of a surprise; we accidentally made a volcano,” laughed Robinson.

READ: Military kid opens doors to STEM for young women of color

The extracurricular STEM program, Rosie Riveters, was the dream of the group’s executive director, Brittany Greer, who grew up with a poster of the WWII-era icon on her bedroom wall.

She started the nonprofit to get preschool to middle school girls engaged with STEM activities, hoping that the young memories may bridge the gender gap in the field one day. According to Rosie Riveters, in 2019, women made up only 27% of the science and engineering workforce in the U.S.

“What we want them to do is know that with the confidence in themselves, they can go into any field and innovate, change and participate in it,” said Greer. “The world of possibilities in front of them is huge.”

Armed forces nonprofit Blue Star Families saw Rosie Riveters as a chance to create educational programming for female military children, while also providing jobs as instructors to military spouses who faced employment barriers due to their active-duty lifestyle. According to the 2021 Blue Star Families’ annual Military Family Lifestyle Survey, military spouse under- and unemployment are top issues for families in active-duty service.

The pilot program launched with a sponsorship from Blue Star Families and Boeing last spring at Fort Belvoir. Additional instructors have been hired to expand the program to both Joint Base Andrews in Maryland and the Mayport USO Jacksonville, Florida, at the end of April.

“I’ve never met more human beings with PhDs in my life than in the military spouses that I’ve interacted with,” said Greer. “It’s just unbelievable how qualified and incredible they are. They are such an amazing group of people.”

Ultimately, Rosie Riveters hopes instructors will be able to stick with the program even through deployments or after a Permanent Change of Station.

deployments or after a Permanent Change of Station.

“The goal is they can move into their new location and let us know when they’re settled. Then we would work with Blue Star and the chapter closest to the area they’re located, discuss work opportunities in that region, and then work through neutral partners, so the programs are completely free of charge to families,” said Greer.

Robinson said the opportunity to teach young girls STEM is a dream come true for military spouses, whose careers are often challenged by the needs of an active-duty lifestyle. When the Army sent her husband on deployment, she assumed she’d have to quit her instructor role due to the challenges of serving as a single parent to six kids. She was surprised when program leaders offered to sponsor her childcare so she could continue teaching classes.

“That’s the difference right there between talking the talk and walking the walk,” said Robinson. “That was a very unexpected offer, and I don’t think it’s common for organizations to go to that length of actually supporting military spouses.”

Greer said the nonprofit plans to pay for benefits like childcare through corporate sponsorships. She feels the value of exposing both spouses and military girls to STEM far outweighs the cost of fixing employment challenges.

“We’re really empowering our participants and quite frankly bringing the innovators that we want in STEM fields to the table,” said Greer.