When Melanie Witte heard the news that her hometown, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, would undergo a name change to Fort Liberty in 2023, she said she felt upset. Witte affectionately refers to herself as a “Fort Braggian,” and has lived in the community for almost 25 years — first as a military child and now as the spouse of an active-duty soldier. Her grandfather was also stationed at the installation in the 1960s. When the name changed, Witte said those connected to Fort Bragg lost a part of their identity.

“My children were born here and the first question out of their mouths was ‘do I have to get a new birth certificate that says Fort Liberty?’” she said. “Bragg has certain things about it, and Liberty never fit what it stands for. They’re not only taking down the names, but the history that’s behind that. It’s like pulling away their legacy in a way.”

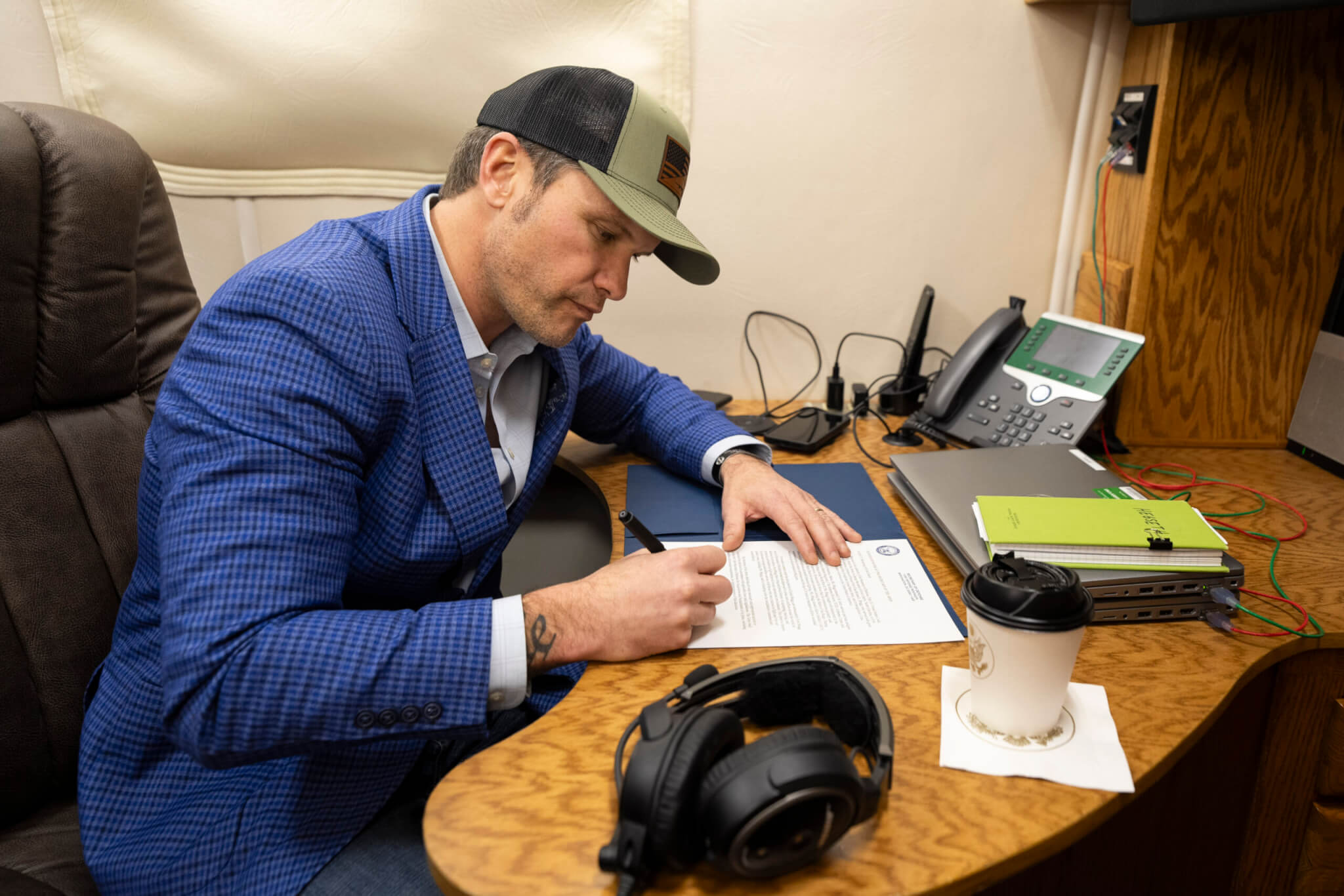

In February 2025, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed a memorandum directing Fort Liberty to be renamed Fort Bragg again. This time though, the premiere Army installation removed its ties to the Confederacy and instead took on the namesake of Army Pfc. Roland L. Bragg, a World War II veteran who was assigned to the 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 17th Airborne Division, XVIII Airborne Corps.

U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Gregory K. Anderson, commanding general of the XVIII Airborne Corps, officiated the post’s renaming ceremony earlier this month, where he provided a brief history about Bragg’s heroism while standing in front of the Silver Star recipient’s children and grandchildren.

“[Bragg’s story] stands as a testament to the bonds forged here in this place, bonds that many who have trained and served here would immediately recognize and feel,” he said. “Over 80 years have passed since Roland Bragg arrived here. Eight decades of soldiers from Fort Bragg have deployed to every major conflict, defending America and her allies across the globe, and they came home to Fort Bragg.”

Eva Daniels is also a military spouse who grew up in the state. She said the removal of “Liberty feels ominous” and that “the Confederacy and its legacy are nothing to cling to.”

“Changing the name back to Bragg doesn’t make sense culturally and is not efficient or cost effective for an administration that claims to prioritize those things,” she explained. “It is ultimately a distraction from other policy changes being forced each day, which will be impactful for military families, our service members and our nation.”

The cost of a second name change is also a concern for Morgan Rose, an Air Force spouse and mortgage loan officer who has been stationed at Fort Bragg for 10 years. Over time, she’s seen how the mortgage rates have climbed, pricing young military families out of off-post living and forcing them into military housing.

“[They live] in substandard housing because the military will not spend money on new housing or renovations,” Rose said. “When I saw they were spending $6 million to change the name [the first time] to Fort Liberty, I thought it was money that could be better spent elsewhere.”

Rose wondered if those who made the decision to change the name — not once but twice — ever considered the people and businesses in the community. She described the renamings as a move that “turned our community into a political pawn.”

“I live up the road from a Fort Bragg Credit Union with a sign that says Fort Liberty Credit Union,” she said. “Are there grants available to support the businesses affected by the name changes?”

Fort Bragg is the Army’s largest installation. The post covers more than 160,000 acres and supports more than 48,000 soldiers, 80,000 family members, 2,000 Department of Defense civilians and nearly 100,000 retirees and their families. The U.S. Army’s Forces Command, Special Operations Command and Reserve Command are headquartered at Fort Bragg. It is also home to the XVIII Airborne Corps, the Joint Special Operations Command and — of course — the 82nd Airborne Division.

Read comments