A group of military parents are raising awareness about dyslexia and its affect on military families using a platform called Decoding Dyslexia Military.

Originating from Decoding Dyslexia, a “network of parent-led grassroots movements across the country concerned with the limited access to educational interventions for dyslexia within the public education system,” the military-specific version caters exclusively to families with a connection to the U.S. Armed Forces.

What is dyslexia?

Decoding Dyslexia defines dyslexia as a language-based learning disability or disorder “that is neurological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities,” such as poor word reading and word decoding.

It is estimated that one in five children suffer from the disorder. There are many misconceptions about dyslexia that have been dispelled, including that it is a form of retardation or that it is linked to a person’s IQ. For example, Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking had dyslexia, with an IQ of 160.

The challenges associated with dyslexia

Hundreds of members with a dyslexic military dependent have connected through a private Facebook group. While they share common challenges with civilian families, such as having a child properly diagnosed, financial strains due to medical bills and private tutoring, and school systems that lack tools to serve neurodiverse children, the constant moving has made military families more vulnerable . This often leads families to either abandon a good school system that offered valuable help in order to keep their family together, or make the heartbreaking decision of not following the service member, thus breaking the family nucleus because the school system at the new assignment does not offer support for dyslexic children.

Brandy Simon chose to follow her military member to Hawaii. However, when her elementary-aged daughter began showing clear signs of dyslexia, Simon says she was shocked to find out that “schools in Hawaii do not offer assistance for dyslexia.” Simon and her husband were on their own, so they resorted to hiring a private tutor and paying for private testing, which put a significant strain on their finances.

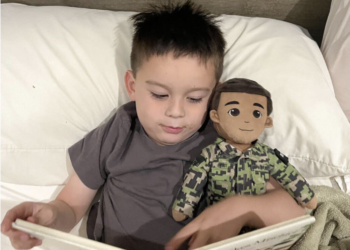

Anna Wilson, Army spouse and mother of four children, was forced to stay behind while her husband moved to a new base because “the Exceptional Family Member Program is failing our kids with education issues.” Her son, Aquilae, now eight years old, was diagnosed with dyslexia in kindergarten. When her husband received orders to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, she decided to stay in South Carolina so her child could keep attending therapy and receive the same school support he’d been receiving, which Fort Bragg did not offer.

The geographic separation has led to financial hardship.

“We are currently having to pay for two households as the military has no way to assist families in our situation,” Wilson said. “We spend near a thousand extra in food, gas, rent and utilities a month. The school our son attends is over $20,000 annually, but the teachers are highly trained in Orton-Gillingham, the recommended intervention for dyslexia.”

Military families face problems with TRICARE and DoDEA

TRICARE doesn’t cover diagnostic, evaluation, treatment, services or supplies (including special education services) for learning disorders, such as dyslexia, according to its website.

“Here in lies the problem,” Betsy Ramirez, whose teenage son Evan was diagnosed with dyslexia, said. “Medical sees it as an educational problem but educational sees it as a medical problem. It’s actually both. We end up paying hundreds or thousands for a diagnosis, on top of the thousands we pay yearly for private tutoring.”

The Department of Defense Education Activity schools prefers not “to use the term dyslexia,” says Alicia Cleaver, whose son KJ was diagnosed with dyslexia, dysgraphia and poor working memory in fourth grade. She knew her son was behind compared to his peers, but DoDEA, after testing him, did not classify him behind enough to provide extra support at school for the first few years of his academic career.

However, “Early intervention, prior to grade three, is preferential due to students falling further and further behind their peers,” according to Louisa Moats and Karen Dakin, authors of “Basic Facts About Dyslexia.”

Advocates call for change

“It’s a national crisis that no one wants to acknowledge,” Ramirez said. “If we truly want to make change in this nation and improve mental health, we could adopt structured literacy methods and train our teachers. We are fighting with schools to teach our kids to read. It’s insane when you say out loud!”

Cleaver adds that military kids are not receiving the support they need.

“We need to screen and identify our students earlier. We need to educate our teachers and administrations about dyslexia. Military kids give so much already and are at risk educationally simply by moving frequently,” she said.

Ramirez, as well as other Decoding Dyslexia Military families, want to raise awareness of the many financial, emotional, and bureaucratic challenges facing military families. The group wants to see significant changes made to how dyslexia is perceived, diagnosed, treated, and managed by TRICARE and DoDEA.

To learn more about Decoding Dyslexia Military, visit the Facebook page. If you have a family member impacted by dyslexia, connect with the Facebook group.

Read comments