Military families are used to plans changing, but not quite like this.

We don’t have a first aid kit, so when my husband cuts his thumb during dinner prep over the weekend, we have to be inventive, wrapping a bit of paper towel around his finger and securing it with the tape we use in the gym to prevent callouses. It wasn’t a major crisis, but it was enough of one to give me pause.

There are some things you prepare for during an international move — like climate-appropriate clothing or making sure you have more copies of orders than you think you need — but there are others no amount of planning could ever uncover. Like countless other families, our PCS from Germany to the U.S. was delayed last week by the global pandemic. We’re already signed out from the medical center on post and hospitals are to capacity right now, as Bavaria has the second-highest rates of infections in Germany.

The DOD order that classified Germany as a Category 3 country reached us mid-morning last Thursday. My husband was four signatures away from clearing post completely. Our final housing check was scheduled for Monday, March 16, and we’d planned to ship our one remaining vehicle the day before wheels up.

[Read FAQs on Travel Restrictions]

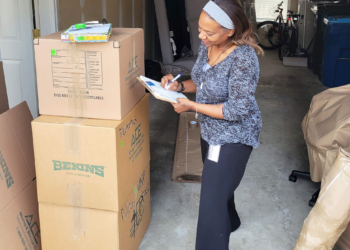

We were 10 days away from leaving Bavaria. Our household goods shipped four weeks ago, and unaccompanied baggage has been gone since the end of January. That means we’ve been living with loaner furniture and kitchen basics from ACS. While we’re appreciative of these things, they’re not our own, which makes the prospects of living here for an additional undetermined amount of time even more unnerving.

We sent everything ahead of time because we wanted to make sure it was there, ready and waiting, for our arrival in D.C. This is a big move for my family as my spouse transitions into a new branch, so I did my best to think far ahead, making contingencies for contingencies. The only contingency I didn’t plan for was a global pandemic

As a military community, there are so many things we’re all willing to deal with on the heels of a PCS. We expect to embrace the suck for a few weeks because we know we’re on the way to something different, something new. For instance, it’s OK if we only have a few towels that we wash ad nauseam, or if we downsize a wardrobe to be just a few pieces. We temporarily make do with limited everything because we expect it’s not going to last — except when none of that happens when we get stuck in a country that’s quickly becoming the epicenter of a global crisis, with no end in sight.

One of the most pressing and challenging aspects of all of this is the fact that everything inside our house is gone. For our move from Germany to Washington, D.C., there are several strict rules in place. We’re unable to ship back kitchen staples, so I’ve been letting the cupboards slowly go bare. Just a few weeks ago, I gifted an assortment of shelf-stable items to our post FreeCycle in the hopes someone might find them useful. Knowing our move was imminent, I didn’t worry that I’d need to have anything on reserve

Following the stop-movement order, I realized we were ill-equipped to handle a mandatory quarantine, should it come to that. So, on Friday, I headed to the commissary to refill cupboards and stock up on some necessary items. Unfortunately, the rest of my installation had the same idea, which meant that several things were already out of stock by the time I arrived. The flux this creates is unnerving. In addition to not having a pantry stocked at all, we have no medicines in the house, nor do we have any of the accoutrements that might make time in self-imposed — or DOD-mandated — quarantine more palpable. Maybe if we weren’t in the throes of an international move, this wouldn’t feel as unsettling. Or perhaps it would. The one thing that all of us are experiencing is there are no clear answers, no defined plans; there’s no way of knowing when we’ll be leaving, which makes planning for the next part of this Army life even more difficult.

We’ve been gone for three years. During that time our families have grown and aged experienced milestones and moments of joy. We’ve had to suffice ourselves with video chats and shared digital albums. For military families, the constant moving means we’re never close enough to our native home bases that we can pop in for a visit over a long weekend. Our time abroad has been challenging because of this, and also because we know there are countless small moments we’ve missed while being gone.

Looking forward to returning home is just one layer of what this delay means. It also puts on hold several professional developments I’ve been working on for months. It upends the schedule for training set by the Army. It loosens the plan we’ve been working on setting into place since receiving our orders.

The thing is, I watched the virus begin to spread. I have a friend who, up until November, lived and taught in Wuhan. While she was on vacation in Thailand, the borders closed, leaving her stuck abroad. She ended up returning to the U.S. because there was no way for her to get back home. In December, I recall thinking how terrible it must be for her having her life upended like that. The irony that I’m now in a similar position isn’t lost to me. But that’s the thing that I keep reminding myself. There are countless other families and individuals who are experiencing situations similar to what’s going on in my world. All I can do, and all we can do collectively, is take it one day at a time. We might be stalled for the foreseeable future, but I know this won’t last forever.

Read comments