In 2021, supreme performance fueled by rapidly ascending high-tech is becoming commonplace outside of information technology. Auto manufacturing, construction, professional sports, and the military are examples.

Specifically, untapping the potential for a preeminent realm of human performance has gained traction in recent decades.

The University of Southern California (USC) Sports & Military Institute in Los Angeles has become a peak performance conduit for elite athletes and warfighters.

“I’ve always been interested in sports and human performance and elite athletics,” said Dr. Leslie Saxon, a cardiologist and the executive director and founder of the USC Center for Body Computing, which uses clinical research to develop technologies used for health care issues.

The USC Sports and Military Performance Institute is one component of the Center for Body Computing. It specializes in connected and wearable sensors to analyze and improve performance. Saxon says she has always been interested in finding the best way to measure load over time in world-class performers, to optimize the individual, and detect early markers for intervention to prevent injury.

The military has been a prime beneficiary of the Institute’s research and expertise. Around seven years ago, Saxon began a dialogue with the Marine Corps at Camp Pendleton about issues related to its human performers or “tactical athletes.” She says the Marine Reconnaissance Training School had been experiencing a high attrition rate during the initial days of training, primarily due to voluntary drops. She spent three years listening to the Marines about the issues and its sense of who these individuals were and then took action.

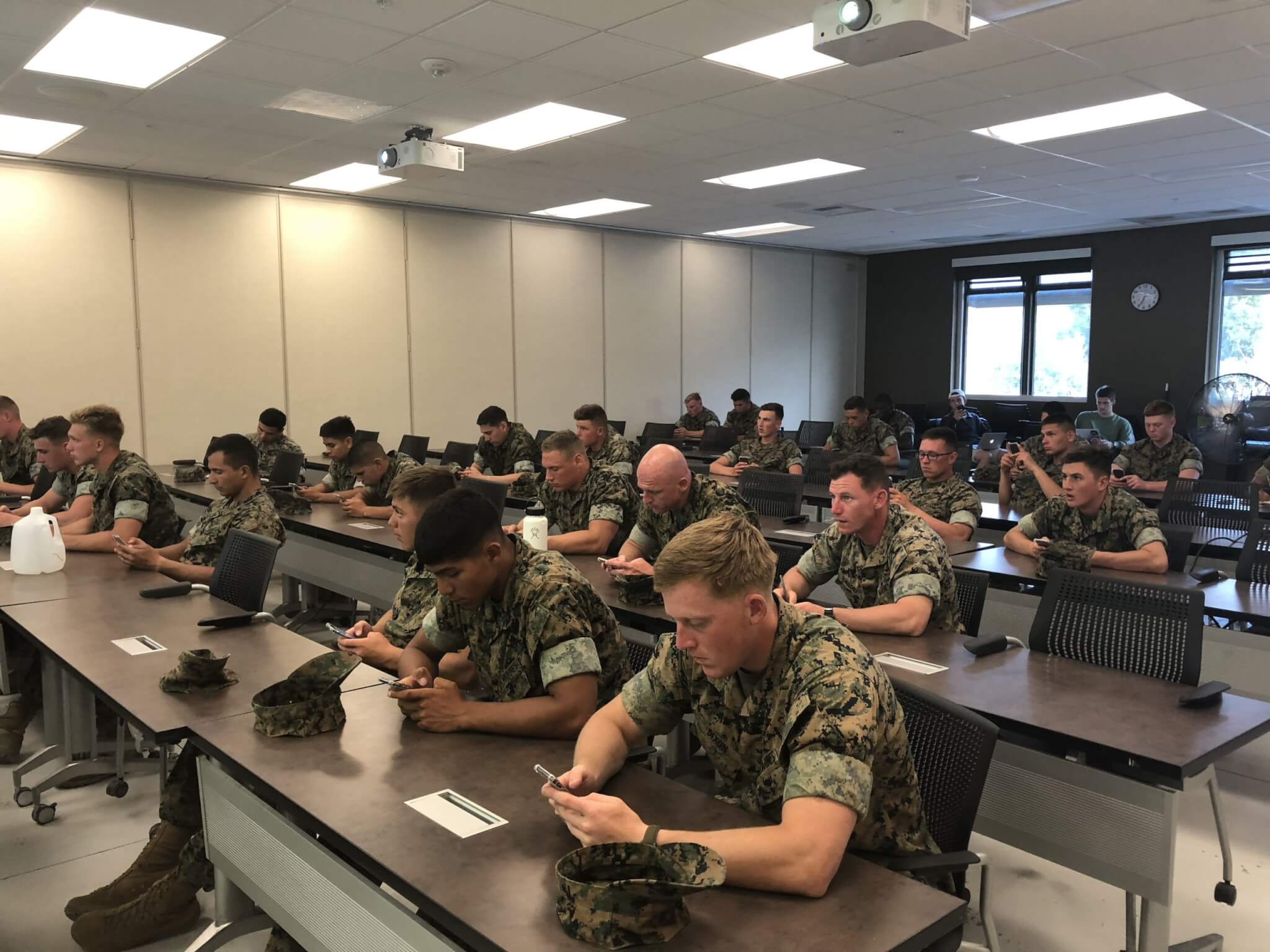

“Over the last two years, USC has conducted several studies with SOI-W (School of Infantry-West) aboard Camp Pendleton, California, focused on entry-level reconnaissance students,” said Capt. Sam Stephenson, the director of communication strategy, operations training, and education command. “The study is reviewing the efficiencies that can be gained by using small electronic sensors to collect and measure biometrics (e.g. heart rate) of students as they progress through training.”

The Marine Corps was dealing with trainees whose attention was divided by the digital side of their lives, which might adversely impact their traditional training, Saxon said.

“We decided to try and quantify the sort-of mental and physical status of these young Marine trainees throughout this early 30-day course,” she said. “And so we decided to kind of leverage that digital life and built a special app, research app, where we could consent and measure their mental and physical status every day, and continuously their heart rate, sleep, diet. Everything to try to understand what the factors were and the load was on these Marines.”

They monitored 150 Marines and three successive training classes day and night. “And we really quantified them … a lot of what instructors thought might be true really wasn’t true.”

The trainees were getting enough sleep and calories in their diet. So it seemed to be a mental problem rather than a physical one. It turned out they were experiencing anxiety when anticipating highly intense aquatic training events.

“We could sort of predict a couple of days before they dropped that they would drop,” Saxon said. Prediction led Saxon and her team at the Institute to find ways to mitigate the attrition and help the Marines. “This idea is that how do we help sort of optimize our warfighters and provide them with sort of high-fidelity, continuous, and individualized assessments … and I think this is such a fascinating field of inquiry with sensors and with strategies, we can really deliver a one-stop-shop.”

Some of the sports entities the USC Sports & Military Performance Institute has worked with include the United States Olympic Committee, the NFL, NBA, the National Football League Players Association (NFLPA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA).

Saxon has spent several years working with football players preparing for the NFL Draft Combine and seeking constructive methods to train skilled position players , like wide receiver or running back.

For instance, the Institute uses technology to pinpoint the most effective mechanics in the first 10 yards of a 40-yard dash — the 40-yard dash is an important Combine test — or how to measure muscle strength.

“Those are really difficult things to get insights into,” Saxon said. “And the technology hasn’t always caught up.”

The Institute employs novel technologies and assesses their worthiness for adoption. An example where data can be exploited to better understand the athlete is a running back.

“His total work is not up and down the field,” Saxon said. “Half of it, or more than half of it’s horizontal, which if you didn’t have a way to measure it, you’d miss it completely. So, is that guy gassed? How do you get that information to help understand what his risk of injury is?”

The NFLPA possesses an enormous health and safety portfolio, and one aspect of that is the use of sensors on players and the corresponding data sets.

“Under the 2020 Collective Bargaining Agreement, we actually established a joint-sensor committee with the NFL,” said Sean Sansiveri, who leads many of the health and safety initiatives for the NFLPA. “Dr. Saxon is one of our appointees on that committee. The one thing that I would want to emphasize about Dr. Saxon and her group is how pro-patient, and thereby pro-player, they are. There have been many instances where we’re debating with the league; issues around use of player data, ownership and the like, and her expertise has been very valuable to us.”

Read comments