Before becoming known as World War I, the largest conflict that anyone at that time had experienced was called simply “the Great War.” America joined three years after fighting began, but U.S. soldiers (commonly referred to as “doughboys”) hurried to answer the call when asked to fight for freedom.

In “The War That Will End War,” H.G. Wells claimed that it was a war for peace, concluding, “Every sword that is drawn … now is a sword drawn for peace.”

However, it was not the “war that will end war” as so many had hoped. But more than 100 years later, there are many who work tirelessly so that the Great War — and its cost — will never be forgotten.

For peace and liberty

“For the first time in American history, they went abroad for no other reason than to win peace and liberty for people they didn’t know,” said retired Navy Reserve Capt. Daniel Dayton, the chair emeritus of the Doughboy Foundation, “and fighting in a fight they didn’t start — and they did it because their country asked it of them.”

Dayton is also the executive director of the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission, which established the National World War I Memorial in Washington.

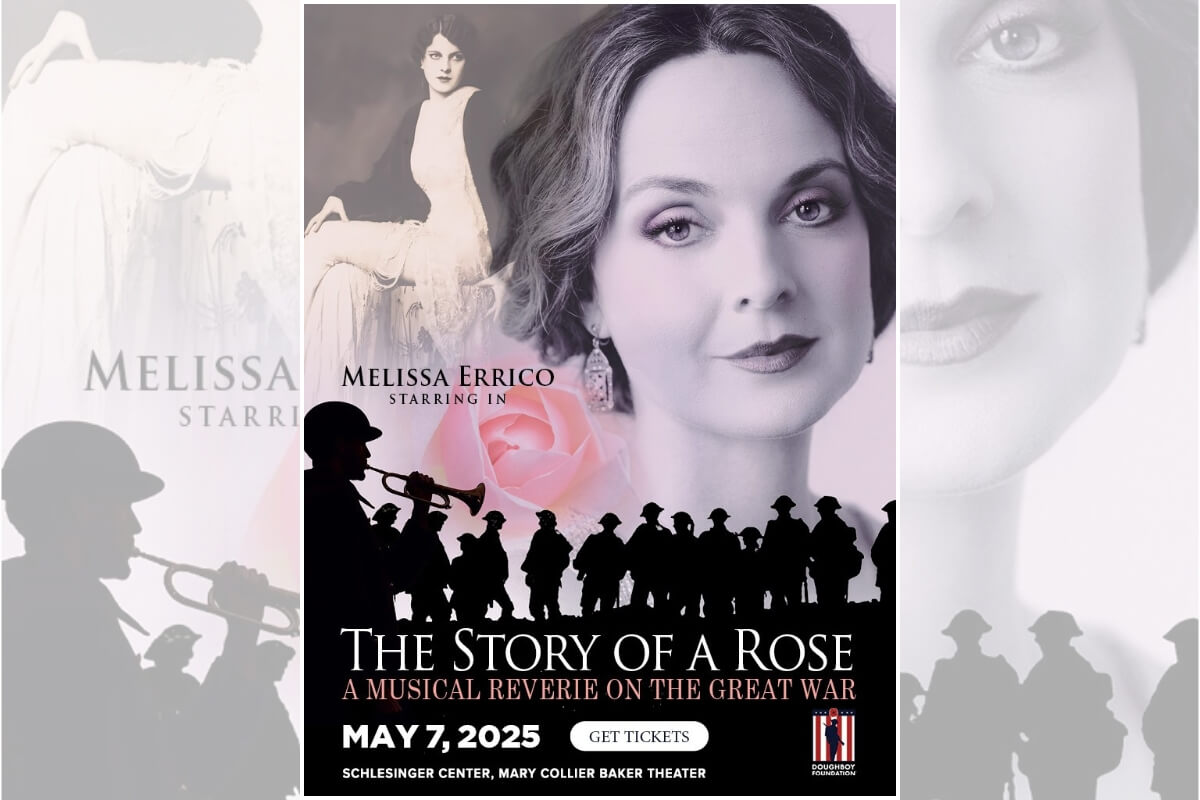

The memorial honors American soldiers, but Dayton knew there was more to be told — the story of a country. After hearing Dayton’s vision, Melissa Errico, a Broadway actress and singer, volunteered to write a musical to tell the story of America at war. Becoming an amateur historian in the process, she researched the reality of war, confronted her own family’s heritage and created a palpable connection with military families, past and present.

The Follies and a personal history

Before the Great War, Errico’s family emigrated from Italy. Having only just arrived in America, her great-grandfather had a fatal heart attack in the customs shed. In a new country and navigating her own grief, Errico’s great-grandmother relied on her two daughters — barely teenagers — to help make a living for the family.

“The first thing that they did at 12 and 13 years old is they went down to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and they got jobs sewing uniforms for the first World War,” Errico said.

One of those teenagers was Errico’s great aunt, Rose, who would later become a Ziegfeld Follies Girl. The Follies were a beautiful crew of dancers, actresses and singers who performed in Ziegfeld Follies productions on Broadway. Rose became the link in Errico’s quest for historical storytelling, resulting in “The Story of a Rose: A Musical Reverie on The Great War.”

“I realized that I had a kind of micro-story that I could illuminate, that could sort of illuminate the larger history. The Follies could play a role in my story through which you could see the emotions of the time, the controversies of the time, because there were pro-war songs, anti-war songs, satirical songs,” Errico explained. “The music of the time took on the flavor of war.”

“There was no radio at the time … the Follies was where you heard this music,” she continued. “So [we] weave together music of the time. … This applies to military families insofar as it’s the sound of the time: It’s the ‘sound of the war’ music.”

Errico used the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) songbook as a guide for what popular songs to include in her storytelling. During the war, the YMCA gave out the AEF songbook, and every soldier made room in his pack for it.

“It’s a pocket-sized book, not very heavy,” Errico described. “American doughboys had to carry up to 60 pounds, which was almost 50% of their body weight for such young men. They had 60-pound bags, and in that 60-pound bag was a soldier songbook, and I have one. … I would say 95% of my songs are replicated [from] that book. … The Follies had incorporated patriotic themes during the war: their songs, the dances, the sketches — [they] celebrated American ideals and celebrated the U.S. military.”

The power in connection

As Errico dove into history, her family opened up about their military experiences, too, none more surprising than her mother pulling a World War I sword out of a forgotten closet. Errico’s grandfather’s best friend died in his arms after a shell exploded in their trench during World War I. After World War II broke out, her mother recalled crying on the stairs when he left to sign up, and the relief she felt after he was told he was too old to serve.

“He was such a proud American,” Errico said. “These Italians were so proud!”

Errico’s own father, a doctor, was drafted into the Air Force during the Vietnam War. However, it wasn’t until Errico undertook this project that he spoke about his military service in Saigon and civilian life after his return.

From hearing stories that have been untold for decades, unburdening a child’s terror and a soldier’s nightmares, the process has been emotional for all of them. Yet that connection links Errico to her family, their past and the military community, and it is powerful.

“I feel that I’m using the language that I understand, which is music and theater, to suddenly make the star of the show the military,” Errico said. “What I understand is the world I’m going to sing through. But in the end I’m gonna understand — finally — them.”

‘The war that will end war’

While the Great War did not “end war” as foretold, the men and women of that generation set an example of honor, patriotism and sacrifice.

“[The musical] celebrates the altruism of Americans of 100 years ago, their willingness to serve wherever their country asked them to serve in honor of peace and liberty without any special compensation,” Dayton said. “They did it because it was the right thing to do. That’s who we were … that’s who we were as a nation.”

“The Story of a Rose: A Musical Reverie on The Great War” — produced by the Doughboy Foundation and presented by the Gary Sinise Foundation — will be performed at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall in Alexandria, Virginia, on May 7, before going on national tour.

Read comments