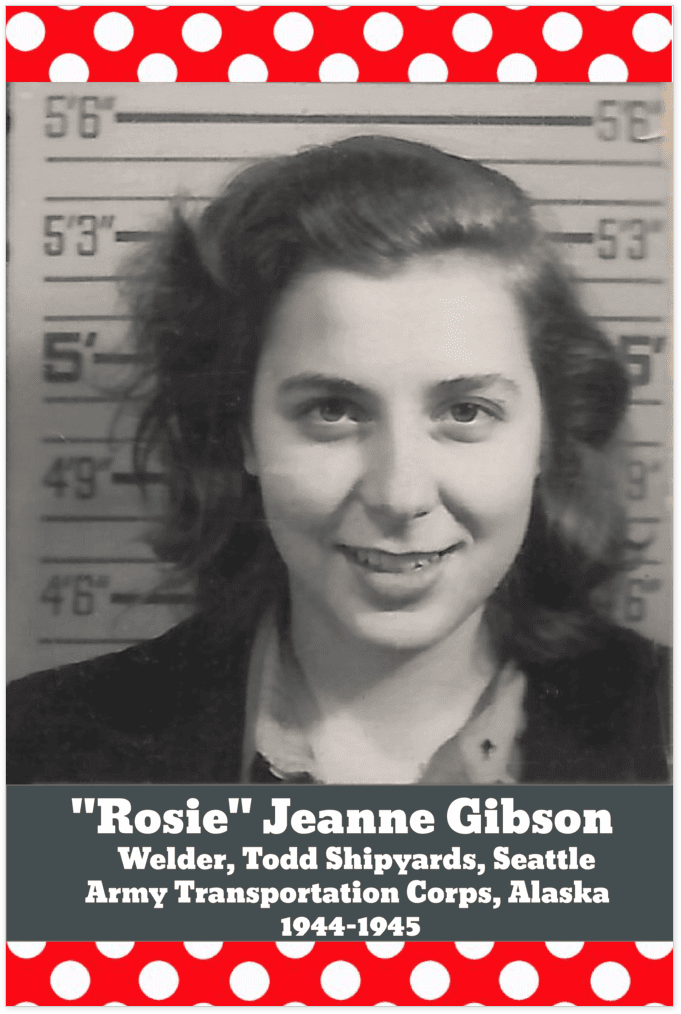

For 98-year-old Jeanne Gibson, one of the last surviving women who contributed to the war effort during World War II, 2024 was a banner year. Raised in the Midwest during an era when women were expected to take small jobs before settling into homemaking, Gibson’s adventures this year — from commemorations at Pearl Harbor to ceremonies in Washington, D.C., and a special flight to Normandy — reflect a lifetime of breaking the mold.

In the summer of 1944, after nearly joining the Cadet Nurse Corps, Gibson boarded a bus to Seattle with her best friend, Esther Harri, for a job at the Todd Pacific Shipyards. Like millions of women now known as Rosie the Riveters, the two young women answered the nation’s call to join the war effort.

Rosie the Riveter, a cultural icon immortalized in the 1942 song by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, embodied women’s wartime contributions. As men left for combat, women stepped into roles traditionally held by men, including producing munitions, aircraft, and other essential materials. Most people today know Rosie as the famous image of a woman flexing her bicep under the words “We Can Do It!”— a tagline that captured the determination of young women like Gibson.

“Everyone was focused on winning the war. It was a good time from a woman’s point of view — it emancipated women,” she said.

At the shipyard, Gibson and Harri worked as welders on the swing shift — an afternoon-to-evening schedule that kept production going around the clock. They carefully fitted and fused massive steel plates for destroyers bound for the Pacific.

“Welding is a lot like sewing,” Gibson said. “It’s a hand movement that is gentle and very careful, like sewing. Some of the terms are even the same — you tack pieces together before welding them, just like in sewing.”

Some 80 years later, Gibson still recalls the precision required as if she had just stepped off the assembly line.

“Tacks in a weld are about an inch long and about a foot apart,” she said. “The hand movement — you hold the welding rod in kind of a clamp, and after you strike your arc, you nurse that arc of molten metal along the seam like you’re sewing it.”

Though their work was hard, camaraderie sustained them. Gibson recalls using their first paychecks to buy long 50% wool underwear for the chilly shipyard nights.

“Being a welder was kind of fun when you’re 18,” she says with a smile. “The men were nice to us — they looked out for us. They were old enough to be our fathers or grandfathers.

After a year, Gibson and Harri moved to Juneau, Alaska, where Gibson worked for the Army Transportation Corps, preparing manifests and hatch lists for ships delivering lumber to build Pacific bases.

“If I hadn’t left and done that, I probably would have married and had children,” she explained. “Being a Rosie gave me wings to say ‘no’ and do things.”

On V-J Day in Juneau, Gibson recalls watching celebrations from her apartment window. “Enlisted men were cutting off the ties of the officers as they celebrated!”

After the war, Gibson briefly returned to Minnesota temporarily and then eventually to San Francisco. She soon encountered the gender discrimination of the post-war economy.

“My file clerk was making $5 more than me because he was a man, so I quit,” she said.

Determined to chart her own path, Gibson earned her undergraduate degree, a master’s and later a Ph.D. in educational psychology all from the University of California, Berkeley. She dedicated 30 years to teaching and helped develop national science curricula with the American Association for the Advancement of Science in the wake of Sputnik.

Her adventurous spirit never waned. In her 40s, Gibson and Harri earned private pilot licenses and joined the Ninety-Nines, a women’s aviation group founded by Amelia Earhart.

Today, Gibson shares her Rosie story as a volunteer at Rosie the Riveter WW2 Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California. In April 2024, she and 26 other Rosies traveled to Washington, D.C., to receive the Congressional Gold Medal honoring the Rosies’ invaluable contributions to a nation at war.

In June, Gibson traveled to Normandy sponsored by the Gary Sinise Foundation alongside other veterans, a Holocaust survivor, and one fellow Rosie. There, she visited Omaha and Utah beaches and was moved by the gratitude of the French people — not just the older generation who lived through the war, but teenagers, children, and young adults.

“They’d shake our hands or hug us, saying, ‘If it weren’t for what you did, we’d either be speaking German or dead,’” she said.

Gibson’s year of travels came full circle as she returned to Hawaii in December to commemorate the anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor — the moment that brought the U.S. into World War II — and set her remarkable life story into motion.

As she reflects on her life and the legacy of the Rosies, Gibson’s hope is clear and as bold as she is.

“The thing I hope carries over is that women are appreciated and paid a fair wage, equal to men. And that people realize our form of government is precious,” she said. “If something can be done, do it — kind of like that Nike commercial!”

For Gibson, life as a Rosie was about so much more than welding, she says. It was about forging a path of independence and having a hands-on role preserving democracy. At nearly 99 years old, she continues to inspire women with her tenacity, wisdom, and firm belief that anything is possible.

Read comments