The head coach paused like a conductor catching an off-key clarinet. He fixed his eyes on a face flushed firetruck-red, streaming with tears. With a heavy mist across their faces, 11 eager preteens just watched their soccer coach instruct the next drill: the mechanics of the long ball. While scanning for distracted gazes, it was the all too familiar look of heartbreak that arrested the coach’s attention.

He blows his whistle and yells, “Take 10!” And then, he says to the player, “Walk with me,” as the others jog to the sideline to grab their water bottles.

“Why are you crying?” the coach asks.

“I was just sad because my best friend from the youth center is moving away, and I will miss him,” replies the player, wiping away his tears.

This distressed 12-year-old, a military child, is not alone in his struggles. The Department of Defense celebrates military children annually during the month of April, reporting in 2022 that more than 1.5 million encounter unique challenges and experiences resulting from their parents’ service.

At the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade, this topic garners widespread attention due to 51% of its personnel having children, which is a staggering 35% higher than the Marine Corps’ average. But it reaches beyond the numbers. The MEB’s mission and location also add levels of complexity to the household dynamics of its Marines, Sailors and civilians. Often, the families share the sacrifice of their service members for the greater good of the nation.

“I fully appreciate the sacrifices of our military kids and their parents,” said 3rd MEB chief of staff Col. Charles Readinger. “Every day, I see these parents doing their jobs at a high level, from coordinating maritime fires to negotiating enemy problem sets to planning for future contingencies. They work long hours and sometimes deploy across the Indo-Pacific. And as soon as they come home, they lead their families as best they can.”

The MEB is headquartered in Camp Courtney, Okinawa, Japan, which lies along the First Island Chain, a critical stretch for geostrategic competition. The brigade provides a scalable, standing, joint capable and forward-deployed warfighting headquarters that is capable of commanding expeditionary advanced base operations, crisis response and contingency operations. This makes the MEB a vital asset for the Marine Corps in the region. MEB families, particularly their children, feel the heavy lift.

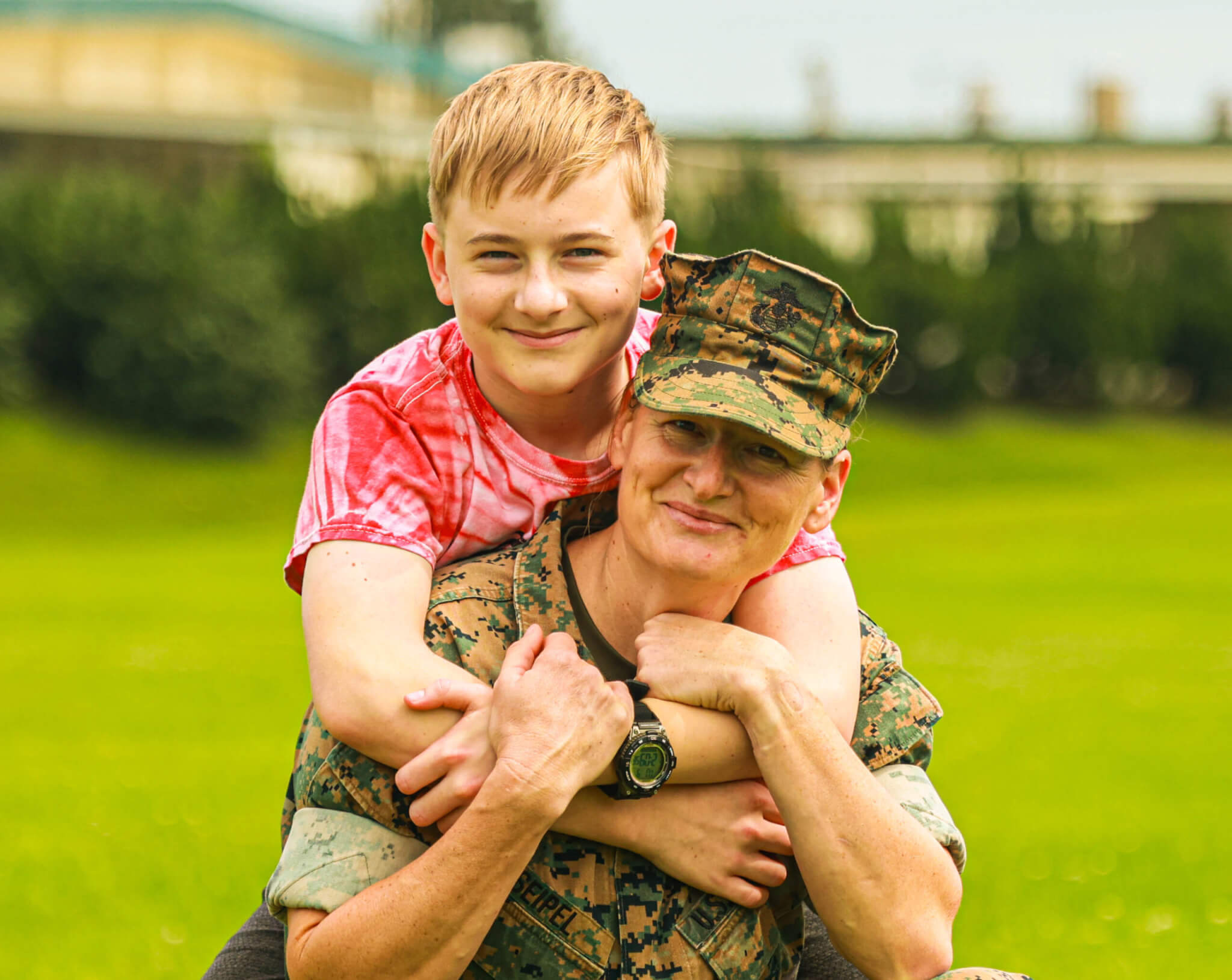

Apart from dealing with a high operational tempo, Okinawa poses a number of challenges for these children. On the same base where they practice sports, meteorologists periodically warn of radical typhoons and tsunamis possibly striking their homes. Harley Seipel, 13, remembered how “the waves splashed along the cliff and went over onto the house,” and Fiona Blyleven, 8, described the natural threats as “very scary.” Other growing pains include a language barrier with the native population, a seven-thousand-mile distance from their loved ones in the American homeland and island-wide mobile phone alerts warning citizens to seek shelter as ballistic missiles are launched in nearby airspaces.

When Maj. Marcos Azua, the comptroller for 3rd MEB, deployed to the Philippines for Exercise Balikatan 23, his son Martin, 8, struggled with losing the things his Dad would normally do and recalled this moment in time as “long and hard.”

Olivia, the 17-year-old daughter of 3rd MEB commander Brig. Gen. Trevor Hall, regretfully acknowledged the missed birthdays and holidays swallowed by long work hours and deployments. While she momentarily admired the stability of civilian life, this is the life she has always known and would never change, and her family fights for their relationships through every obstacle.

“Dad’s been on the most trips and Mom’s been on two,” said Sam Blyleven, 5, who is keeping a tally on his parents’ deployments. “When I was born, we used to have a lot of hangout time which went down since he got older and had to go on more work trips.”

Sam’s parents, logistics planner Lt. Col. Melissa Blyleven and operational planner Lt. Col. Scott Blyleven, help the commanders of 3rd MEB and III Marine Expeditionary Force reconcile matters of regional security in a contested environment. Their pivotal roles keep them on the move.

Like Sam, some 3rd MEB children see both of their parents come home in uniform. When a dual-military couple is deployed simultaneously, their children must live with interim caregivers, such as friends or extended family. These separations can strain relationships and stability in the home.

Time and effort from these parents come in higher demand at this command, as they represent the Stand-in Force of the Indo-Pacific, ready to respond swiftly to any crisis or contingency.

It is not all hard times. The strength of the military child is their resilience. Like a genetic trait coded into their DNA, they quickly learn and adapt to their environments.

“I’ve learned how to adapt to changes and how to appreciate the things that I have when I have them,” said Olivia. “In other places, I kind of struggled with making connections, but now that I live in Okinawa and I have a whole bunch of friends, I really appreciate them because I know what it’s like to not have them.”

Okinawa’s cohesive military community strikes a heartwarming chord for Olivia, who has moved six times. Being the most intimate of any she has experienced, the island community has introduced her to many new friends.

In the same way, 11-year-old Hanna Blyleven appreciates what her nomadic journey has taught her about relationships.

“It’s made me a friendlier person, I think,” Hanna said. “I have to get used to making friends really, really quickly.”

Okinawa is more than just another duty station, as the island offers a one-of-a-kind experience for those that get to call it home, even if only for a little while.

While the team at 3rd MEB rehearses warfare and crisis response, their children engage with Japanese locals, see history in real life, snorkel with exotic fish and bike independently to their piano lessons, protected by an uncommonly low crime rate.

After eagerly describing his experience at the Ryukyu Lantern Festival sponsored by Marine Corps Community Services, Martin proudly recounted his snorkeling encounter with the “black, yellow, blue and white” Hawaiian state fish.

Fiona and Sam also enjoy visiting the beaches surrounding the island, where they can catch scrambling hermit crabs and race through the clear, electric blue surf.

“I love the food. I love the sushi and the noodles,” said Olivia. In 2018, the Journal of Maritime and Island Cultures pointed to the local food as a leading factor in the high life expectancy of women in Okinawa. Other contributors included climate, culture, closely-knit social organizations and active lifestyles, all ingredients of Olivia’s pleasant Okinawa experience.

With the highs come the lows, and while every home in a new place brings the thrill of discovery, it also means the ice-cold sting of departure from a loved one or a dear friend.

In the ever-transient military life, these experiences are routine. On average, military children move every two to three years and change schools six to nine times from the start of kindergarten to their high school graduation. Venturing across the United States and abroad, Harley has found home from the sun-soaked beaches of California to beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, in the snowy winters of Pennsylvania and beside the mile-high skylines of New York City and from the jungles of Japan to the foggy hills of the Czech Republic. Harley shared his sage wisdom for those facing transition and difficult goodbyes.

“First, write a letter explaining why your friend was really good and the great things about them,” said Harley, with a soft smile. “Send it to them the day you leave. And then remember that there’s a slight chance, though still a chance, you’ll meet them again. If possible, keep contact and know that you’ll meet new friends later down the line.”

Harley’s profound insight can be attributed in part to his parents, who are seasoned Marine leaders. He is the son of dual-military couple Col. Petra Seipel and Col. Patrick Seipel, who serve as senior officers in charge of supply and logistics at 3rd MEB and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. They have handed their son the tools of a future military leader.

Despite what they endure, many military children still feel equally called to serve. Compared to children of civilians, military children are twice as likely to join the military, reports the Military Child Education Coalition.

“Jets are super cool, and I want to be a fighter pilot,” said Hanna, inspired by the book “Jet Girl” by Caroline Johnson, an F/A-18 Super Hornet weapons systems officer. “I really like roller coasters and jets are a lot like roller coasters. They go really fast.”

Meanwhile, Hanna’s brother, Sam, hopes to “carry the guns” with a ground combat force, and Harley aspires to the military’s more technical fields, where he could pursue “coding, photo-editing or 3D animation.”

In their own ways, military children already simulate military training, whether they are imitating Navy Sailors conducting emergency exits off a ship with Sam or stalking each other through the neighborhood during epic Nerf battles like Martin.

Military life can evoke a transcendent sense of pride, commitment and service to our country. Every time a child sees their parent in the Marine Corps’ crisp dress blues or hears their parent’s stories about dodging through the woods with a rifle alongside the finest warfighters, a natural awe is formed. For many of them, that awe becomes a dream. And that dream becomes a military career even greater than anything they had imagined.

Heavy mist turned to warm drizzle as each young athlete dissected an orange-coned course, dribbling their soccer ball in rhythmic flow.

“Are you ready to get back to practice?” asked the coach, an active-duty Marine and former military child himself.

“Oh, I’m okay now,” the player said to his coach, while he fiddled with a soccer ball at his feet.

Between the seams of adversity and adventure, military children become the best citizens of tomorrow, full of bravery, respect, ingenuity, responsibility, empathy and resilience.

And for every tear spilled, like bitter medicine, over a departing friend or a deploying parent, military children earn steel stripes on their soul, forever branding them as the strong and reminding them of the cost of freedom.