An organization that works to affect policy change for military spouses released findings from its 2023 white paper.

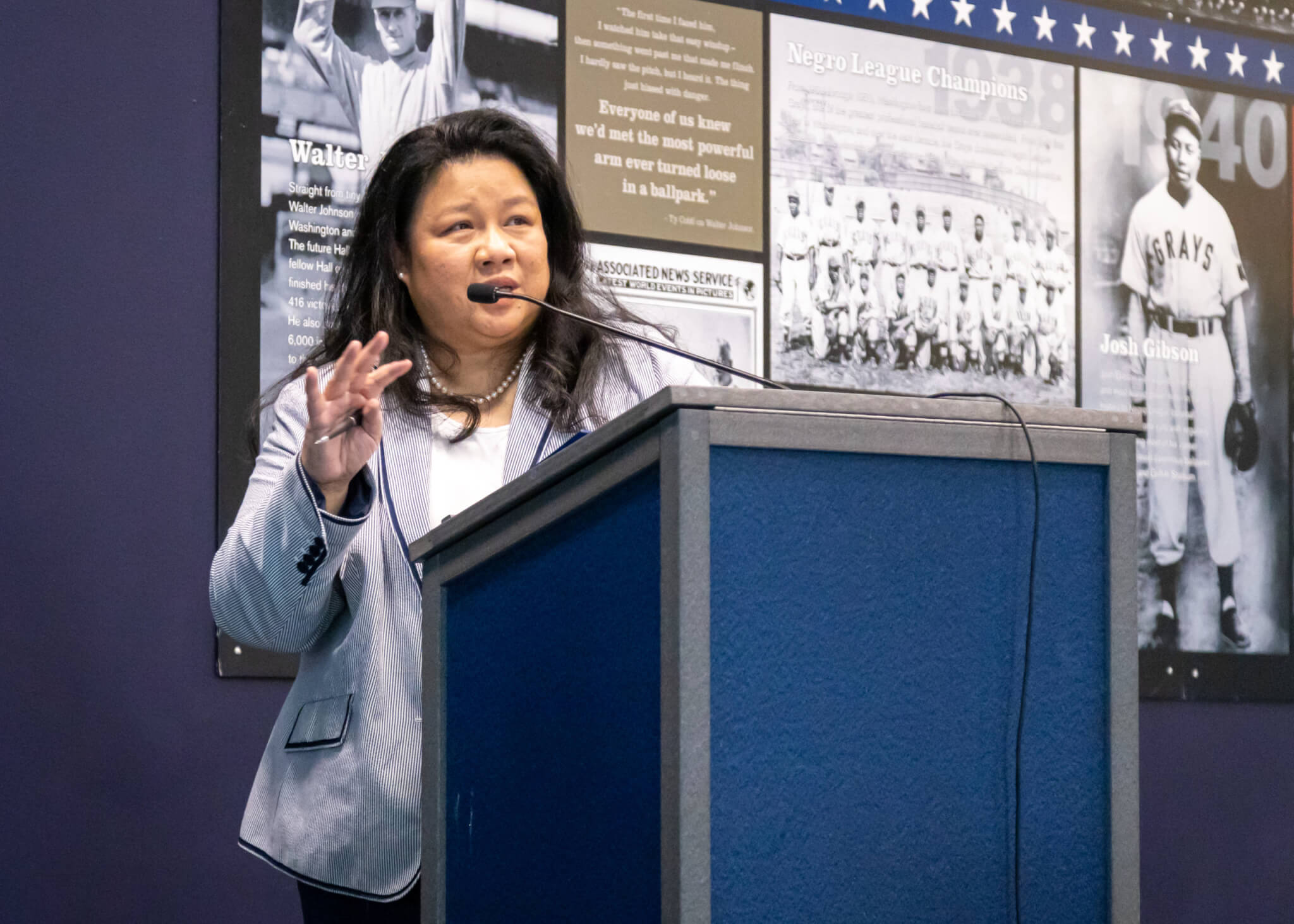

The National Military Spouse Network (NMSN) — the preeminent networking, mentoring and professional development organization committed to the education, empowerment and advancement of military spouses, introduced a number of recommendations in its status report “because the military spouse employment puzzle is far from solved,” according to Sue Hoppin, president of NMSN.

Here are three takeaways from this year’s anniversary white paper:

#1: Federal careers help — two birds, no stone

“I think the big takeaway for me was that we still have a lot to do when it comes to federal employment,” Hoppin said. “If we’re going to really make any movement around the spouse unemployment rate … there’s going to have to be a very concerted attention paid to federal opportunities.”

Among the seven recommendations proposed by the 2023 NMSN White Paper presented by USAA is “Increasing the number of military spouses working in the federal government, but it is one that is often overlooked because there are existing federal employment opportunities, like military spouse hiring preference.

Military spouse preference does not always bump spouses to the top of the list when competing against veterans; it only covers spouses for one year after an active-duty member retires and can be avoided by only posting a job for a few days if a hiring authority already has someone in mind for the job.

NMSN’s white paper supposes that these existing opportunities are not as focused on getting military spouses into lucrative careers as much as they are boxes to be checked to provide military spouses jobs. The distinction is important as these efforts currently stop after a spouse is hired and little is done to ensure they retain their federal job long enough to pursue a true career.

“Increased representation in the federal workforce would both fill existing federal recruitment and representation gaps with talented employees, while also improving military spouse career portability, longevity, and long-term upward mobility,” the white paper states.

#2: NMSN recommendations are plentiful; DOD actions are slow

Military spouse unemployment continues to hover at more than 20% and is a perennial issue for military families. And little progress has been made over the past decade.

Over the past four years, NMSN has made 18 recommendations to combat military spouse unemployment, coupling anecdotal accounts with data-informed solutions. Of those, only three have seen “significant movement,” nine experienced “some movement,” seven had “no movement” and none have been completely resolved.

NMSN’s recommendations are often simple, low or no-cost solutions, aimed at making legislative change, with one of the areas of significant movement focusing on “studying military spouse financial vesting programs and their ability to access these benefits.”

Although this section of the white paper was intended to summarize the NMSN recommendations, it highlighted how little progress the DOD, Congress, employers and the military spouse community have made on some of these issues. Awareness on the topic has been raised, but existing solutions don’t seem to be making a dent.

#3: NMSN doesn’t wait on government action

Hoppin said she has been overwhelmed by the response to the 2023 white paper recommendations, which mostly includes messages of reflection. She often gets private messages on LinkedIn and Facebook from military spouses and community members thanking NMSN for advocating for military spouse professionals, and “for taking the time and the care to talk about the arc of spouse employment where we came from, before focusing on where we have to go.”

Many organizations focus on solving a problem one way, but NMSN’s white paper highlights that combating military spouse unemployment will take a multi-prong approach because military spouses don’t have just one type of career. This requires Hoppin and NMSN to stay at the forefront of not only the current issues faced by military spouses, like transferring professional licenses or career portability overseas but also to predict future challenges.

“I think there’s a shift that’s occurring. And I think the shift is in how different generations view a successful career,” said Hoppin.

And the paper closes on that theme. Generational differences will change the future of work, something that Hoppin and the employment industry have been honed in on for years, but the DOD is slow to keep up, to its detriment. Because, as the white paper states, fixing military spouse employment issues is not a nice idea but an essential operational mission, because “the strength of our All-Volunteer Force depends on it.”

Other 2023 NMSN White Paper recommendations:

- Compile and streamline access to critical career information needed by military spouses;

- Modernize military spouse employment programs, resources and delivery systems for today’s military spouses;

- Expand military spouse access to employment assistance support services from one year to three years after the service members transition from the military;

- Create Congressional career pathways for military spouses through fellowship or internship programs;

- Develop a shared lexicon, facilitating clear communication within communities, as well, as among service providers, advocates and lawmakers;

- Remove barriers to public and private partnerships.